How

core memory works

The

most common form of core memory, X/Y line

coincident-current – used for the main memory of a

computer, consists of a large number of small ferrite (ferromagnetic

ceramic) rings, cores, held together in a grid structure

(each grid called a plane), with wires woven through the

holes in the cores’ middle. In early systems there were four

wires, X, Y, Sense and Inhibit,

but later cores combined the latter two wires into

oneSense/Inhibit line. Each ring stores one bit (a 0 or

1). One bit in each plane could be accessed in one

cycle, so each machine word in an array of words was spread over

a stack of planes. Each plane would manipulate one

bit of a word in parallel, allowing the full word to be read or

written in one cycle.

Core

relies on the hysteresis of the magnetic material used to make the

rings. Wires that pass through the cores create magnetic fields. Only

a magnetic field greater than a certain intensity ("select")

can cause the core to change its magnetic polarity. To select a

memory location, one of the X and one of the Y lines are driven with

half the current ("half-select") required to cause this

change. Only the combined magnetic field generated where the X and Y

lines cross is sufficient to change the state; other cores will see

only half the needed field, or none at all. By driving the current

through the wires in a particular direction, the resulting induced

field forces the selected core’s magnetic flux to circulate in one

direction or the other (clockwise or counterclockwise). One direction

is a stored 1, while the other is a stored 0.

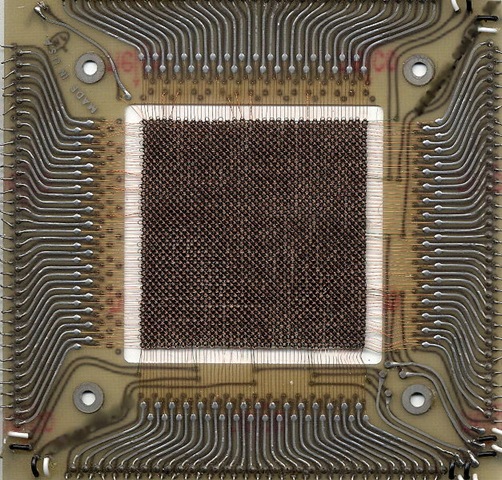

Close-up

of a core plane similar to the one shown at top. The distance between

the rings is roughly 1 mm (0.04 in).

The green horizontal wires are X; the Y wires are dull brown and

vertical, toward the back. The sense wires are diagonal, colored

orange, and the inhibit wires are vertical twisted pairs.

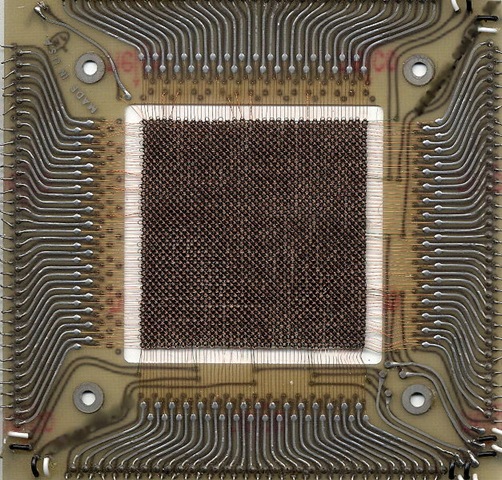

Close-up

of a core plane similar to the one shown at top. The distance between

the rings is roughly 1 mm (0.04 in).

The green horizontal wires are X; the Y wires are dull brown and

vertical, toward the back. The sense wires are diagonal, colored

orange, and the inhibit wires are vertical twisted pairs.

Close-up

of a core plane similar to the one shown at top. The distance between

the rings is roughly 1 mm (0.04 in).

The green horizontal wires are X; the Y wires are dull brown and

vertical, toward the back. The sense wires are diagonal, colored

orange, and the inhibit wires are vertical twisted pairs.

Close-up

of a core plane similar to the one shown at top. The distance between

the rings is roughly 1 mm (0.04 in).

The green horizontal wires are X; the Y wires are dull brown and

vertical, toward the back. The sense wires are diagonal, colored

orange, and the inhibit wires are vertical twisted pairs.